Listen to this article

We are in the middle of the olive campaign and the oil mills are starting to work.

In the first place, it has been costly to determine the specific date, day and time of olive harvest since you have to be aware of both the weather, whether it rains or not, along with the analytics to see the state of the olive.

The first day begins with the set-up of the machines and with the typical and necessary failures and adjustments at the start of the campaign. The noises of the tapes are the first that accompany us in these days full of stress. There are mill masters who lose up to 5 or 6 kilos in the campaign, due to the stress of the first oils.

When it comes to cooperatives or mills with maquilas, the tension and stress is multiplied, due to the interaction with the partners or farmers who take their olives to the mill.

One of the most complex difficulties encountered by cooperatives or mills that work with farmers, making their own oil with their olives for self-consumption, is the relationship with the partner or farmer.

Every year, the farmer sees how the olives that he takes to the mill are different, however he always wants the same yield. That is to say, a farmer carries, for example, 600 kilos of olives a year and they give him 80 liters of oil in exchange, after paying the cost of grinding, more packaging, more filtering if he so wishes. Now, the following year, he can take 700 kilos of olives and they can give him 60 liters of oil, which has been the result of making his olives. And in this way, the formula for delivering olives and oil that they give me in exchange can change in a way that is totally incomprehensible to the farmer.

The person in charge of the oil mill or cooperative does not fail to explain to the partners or farmers who have brought the olives that the yield is different depending on the year, and that what varies between the kilos of olives and the oil that is delivered is fundamentally the Water. The explanation is repeated over and over again, but the farmer does not understand or is not convinced, and they create doubts and mistrust of the factory.

The factory, in turn, is desperate, because if it is already painful to deliver less oil than in other years, it sees how its "customers" or partners leave angry, or devastated, and worst of all, it understands because it sees that they do not understand the arguments of the factory owner. This significantly increases early campaign stress.

We are going to try from ESAO to make the farmer who owns the olive grove understand how the yield will be what determines the amount of oil that they are going to deliver to me, both in the cooperative and in the oil mill that works in maquila. Let's go to a real scenario of a farmer who took some large olives, well swollen and weighing 662 kilos, to an oil mill that carries out maquila, and they return 70 liters of oil. The farmer is indignant, because they seem to him very few liters of oil, and the previous year they had given him 80 liters of oil for 550 kilos of olives. The year in question, it has been raining the days before the collection. Let's see what has happened.

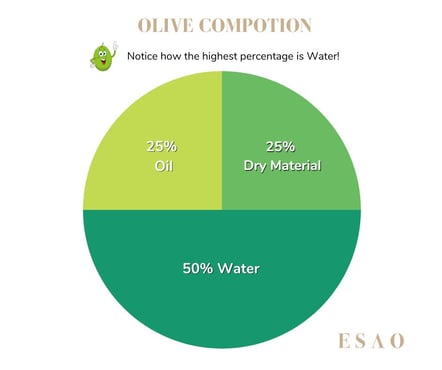

Composition of the olive

In the first place, we are going to know what we deliver when we deliver the olives that we carry, that is, what an olive is made of, in a basic way.

Well, each olive is made up of:

1. Oil 25% (Fat matter)

2. Water 50% (moisture)

Dry matter 25% (stone, skin, pulp)

This means that the weight of our olives is related to the three components above.

As we see, the highest amount is water.

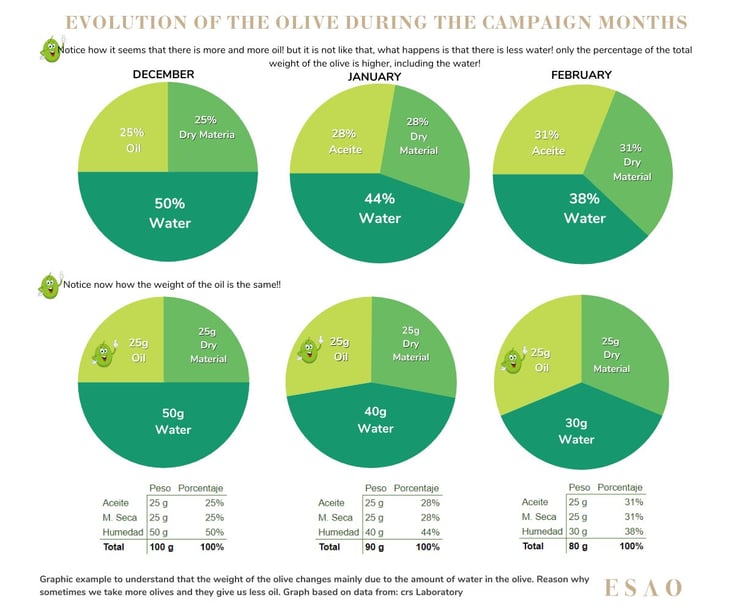

Well, if we have a week with rain for example before picking the olives, because the water content will be higher than if we pick in a week where it has not rained at all previously, we will also see even from the outside that the olives are not so "fat" It won't be that heavy.

This means that when my olives are crushed in the oil mill, the part of solids plus the part of humidity will be eliminated, since it is about extracting only the oil.

What will cause the weight of the olive to vary and the amount of oil will be mainly water, since it is the component that is found to a greater extent.

The amount of oil, if I always pick my olives on the same date, will not change as much, since once the oil has formed inside my olive, and has reached its highest point, this oil will no longer increase , although I pick the olives in January or February. What can change is the amount of water, and the weight, but not the amount of oil, since the oil on a certain date is already "done" inside the olive and will not increase.

For this reason it is very important that the farmer knows what weight his olives have, on dry matter, that is, by removing the water beforehand.

We have the possibility of using precision analyzers that facilitate this work, such as an accredited NIR and backed by an accredited Soxhlet, and this is a guarantee of maximum reliability and, therefore, would help to put an end to discrepancies between farmers, harvesters and industrialists, partners and cooperatives. The NIR tells you the amount of moisture and fat that your olive has, both in the whole olive and prior to grinding and after passing it through a small mill that analyzes your sample.

The price of these analyzers is high, although it would help alleviate confrontations.

However, this is independent of whether the "client" understands the concept of yield on dry matter, that is, without counting the humidity that the olive carries.

In the case of the previous example, if the farmer has brought 662 kilos of olives, and has extracted 70 liters of oil, it means that he has needed approximately 10 kilos of olives to produce 1 liter of oil.

The average for olives of large caliber and high yield is 5 kilos of olives for a liter of oil, however, the average for olives of smaller caliber or lower fat yields can reach up to 14 kilos, with which the 10 kilos for a liter of oil in the example, would not be something out of the average, knowing that we do not know the variety of olive and that the week of the harvest there was rain.

It is quite different in wine, where the average rule is that with 1.3 kilos of grapes it is easy to make 1 liter of wine.

In both cases, but especially in olive oil, it is important to know and also take into account the industrial yield, that is, the result of subtracting from the total yield the losses suffered by the mill when extracting the oil. This is due to the fact that as they are exclusively physical or mechanical processes, that is, grinding, beating and centrifugation, without adding any solvent, it is impossible to extract 100% of the oil contained in the olive. Therefore, not applying this corrector would mean losses impossible for any oil mill to bear. Normally we speak of 1 or 2 points of subtraction for the industrial yield.

So, the important thing is to understand that yields must be worked out knowing and differentiating whether we are talking about yield on dry or wet matter, and we are approaching reliable data every time we talk about yield on dry matter (that is, without moisture, discounting the part of water that my olive carries specifically, which will be different depending on the campaign in question).

Let's give an example of what percentages would be on the same olive:

– (RG smh) Total fat content on wet sample > 20% (Amount of oil as found in the olive)

– (RG sms) Fat richness on dry sample > 40% (Amount of oil that the olive has without taking into account the water)

– Olive moisture < 55% (Amount of water contained in the olive)

In all three cases, the amount of oil in the olive is the same, however we see how the percentages change, and the person responsible for these changes is only the humidity.

This means that the index of fat on dry matter (sms) is not influenced by the amount of water that the olive contains and that is why it is the ideal and most reliable parameter to know the real oil that the fruit contains. And it is for this parameter that the farmer must be paid, since it is the oil that the olive contains.

Here you have a video of a continuous NIR on the tapes. Observe how in the data the highest percentage is humidity.

In this video from the Olivarum laboratory, an NIR is shown in a specific sample of whole olives. Observe how in the data the highest percentage is that of humidity, which has been accredited by ENAC, the national quality accrediting entity, the maximum accreditation for analysis of foss olivescan II and the price could be around 50,000 euros.

.png)